Note: We highly recommend reading this post on the web by clicking here, since most email clients will clip this article due to its length.

Rainbow graffiti in Helsinki, Finland saying ‘Pride was a riot. From Wikicommons.

Like our journalism? Help us keep doing it. Support our winter fund drive.

“What is the horror of swift death by the axe, compared with lifelong death from hunger, cold, insult, cruelty, and heart-break? What is swift death by lightning compared with death by slow fire at the stake? A city cemetery could contain the coffins filled by that brief Terror which we have all been so diligently taught to shiver at and mourn over; but all France could hardly contain the coffins filled by that older and real Terror—that unspeakably bitter and awful Terror which none of us has been taught to see in its vastness or pity as it deserves,”

— Mark Twain, 1889

“They murdered folks in Alabama, they shot Medgar in the back.

Did you say that wasn’t proper, did you stand out on the track?

You were quiet just like mice. Now, you say that we’re not nice.”

— “It isn’t nice,” civil rights movement song

Our daily lives are filled with unacknowledged victories, won by immense bloodshed against oppression. Throughout much of history those making any move towards liberation, any meaningful social change have faced scolding and lectures by the gentry for daring to raise their fists. In an effort to silence any action that might threaten their power, the same gentry have created an artificial debate around the science of “nonviolent” revolt. Their assertion is that (an often misunderstood or deliberately misportrayed) version of nonviolence is the only way forward. This debate is, like so many others they manufacture, little more than a tool used to silence radicals.

Debates over the role of force can be, and often are. held in good faith by those who acknowledge the need for immense change to capitalism’s unnatural hierarchies. But to a much greater extent, especially as capital finds itself in crisis through mass resistance, proponents of a tame version of “nonviolent” change will find themselves arguing from the megaphone of leading, international institutions, which produce some of the most powerful elites in history, that the public needs to quiet down and resist civilly. This is in spite of the fact that many of those elites are themselves instigators of mass murder, often outright war criminals, even under current, deeply-flawed international laws.

This is hardly new. Karl Marx in his 1850 Address of the Central Committee to the Communist League famously railed against the moderates of the time who asked for quiet, tepid revisions to the oppressive state, especially when it is used to disarm the working class.

“At the moment, while the democratic petty bourgeois are everywhere oppressed, they preach to the proletariat general unity and reconciliation; they extend the hand of friendship, and seek to found a great opposition party which will embrace all shades of democratic opinion,” Marx declared in the 1850 speech. “That is, they seek to ensnare the workers in a party organization… Such a unity would be to their advantage alone and to the complete disadvantage of the proletariat… Under no pretext should arms and ammunition be surrendered; any attempt to disarm the workers must be frustrated, by force if necessary.”

It is important that those who seek to crush liberation today must sanitize and erase the movements of the past, particularly the civil rights movement. They conflate its nonviolence with passivity and a lack of disruption. Some, like 50501, do this explicitly. In doing so they even get nonviolence wrong. The civil rights movement had its own disagreements and differences with other groups in the wider Black liberation struggles, but its use of nonviolence was explicitly a set of highly disruptive tactics aimed at making injustice impossible to maintain.

Its groups and organizers intentionally defied laws and police while refusing “moderate” offers of compromise. “It isn’t nice” was one of their songs for a reason. Today, there’s good odds those organizers and activists would be condemned as “provacateurs” and turned over to the police by those who invoke their memory to shut down militant demonstrations today.

Their attitudes on armed defense — and even violence — were also much more complex, rooted in the reality of the cold terrors they faced. It is also much more complex than portrayed in today’s liberal mythology.

Martin Luther King, Jr., while not expressly advocating violent revolt himself, nevertheless refused to condemn tactics used by others in the fight for Black liberation, especially in his later years.

“It is not enough for me to stand before you tonight and condemn riots. It would be morally irresponsible for me to do that without, at the same time, condemning the contingent, intolerable conditions that exist in our society,” King said in his 1968 lecture The Other America. “These conditions are the things that cause individuals to feel that they have no other alternative than to engage in violent rebellions to get attention.”

”And I must say tonight that a riot is the language of the unheard,” King continued to the audience of high schoolers in Grosse Point, Mich. “And what is it America has failed to hear? It has failed to hear that the plight of the negro poor has worsened over the last twelve or fifteen years. It has failed to hear that the promises of freedom and justice have not been met. And it has failed to hear that large segments of white society are more concerned about tranquility and the status quo than about justice and humanity.”

In 1965 King even pointedly refused to condemn Annie Cooper, a Selma, Ala. woman who punched the notoriously racist sheriff square in the face and knocked him to the ground, noting that her actions were clearly “provoked” by his racist violence.

In Charles Cobb’s seminal book on the role of armed resistance in the struggle for Black liberation, especially in the American Civil Rights Movement, This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed, he recounted how journalist William Worthy stumbled upon two firearms in King’s house. The civil rights leader noted these were “just for self-defense.” Another activist described King’s home as “an arsenal.”

Cobb holding a copy of his book This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed. Photo by Deborah Menkart, from Wikicommons.

“The claim that armed self-defense was a necessary aspect of the civil rights movement is still controversial,” Cobb, a legendary journalist and former Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) field secretary, wrote. “However, wielding weapons, especially firearms, let both participants in nonviolent struggle and their sympathizers protect themselves and others under terrorist attack for their civil rights activities. Their willingness to use deadly force ensured the survival not only of countless brave men and women but also of the freedom struggle itself.”

He lays out a multitude of examples, like the heavily-armed Deacons for Defense and Justice group that mobilized against segregation and worked closely with civil rights organizers.

“If we had a picket line, these guys were standing on the corner, on both sides of the street,” CORE organizer Fred Brooks recalled. “Wherever we went it was like a caravan; these guys in their pick-up trucks with their high-powered rifles.”

Renowned radical civil rights organizer Fannie Lou Hamer put it bluntly: “I keep a shotgun in every corner of my bedroom, and the first cracker even look like he wants to throw some dynamite on my porch won’t write his mama again.”

Cobb wrote his history to counter the ongoing sanitization of the realities of that struggle. He’s honest about divisions within the movement over the use of armed force, but also emphasizes that fears that armed demonstrations and defense would lead to overwhelming retaliation proved unfounded. Instead, in plenty of cases local segregationist governments folded in the face of them.

“It may be that ‘nonviolent’ is simply the wrong word for many of the people who participated in the freedom struggle and who were comfortable with both nonviolence and self-defense, assessing what to do primarily on the basis of which seemed the most practical at any given moment,” Cobb concluded.

Shortly after the Stonewall riots, according to Susan Stryker’s Transgender History, moderate cisgender gays and lesbians broke off from their queer siblings and formed the Gay Activists Alliance. While they started off more militant than the “homophile” movement that preceded Stonewall, by 1973 the leadership veered away from radicalism in favor of currying favor with the establishment. They pushed out militant activists in favor of working with the political status quo in elections, political campaigning and drawing all their resources towards the gentry. GAA went on to influence the first Pride march years later. Stryker dishearteningly noted how in 1973 trans activist Sylvia Rivera was “forcibly prevented from addressing the annual commemoration of Christopher Street Liberation Day.” While GAA disbanded a year later, their legacy lives on through efforts to whitewash Stonewall and the utilization of the riots’ name to endorse political candidates.

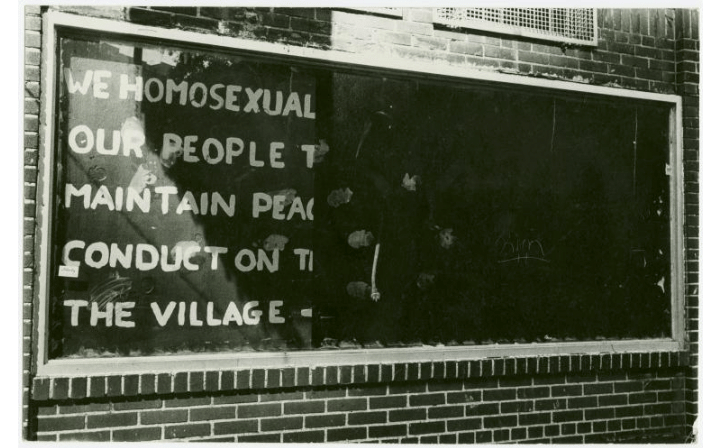

A photograph of the moderate Mattachine Society’s graffiti’d plea to shut down the Stonewall riots in 1969 in favor of passive, ‘peaceful’ protest. It didn’t work. From the Digital Public Library of America.

This is all in spite of Stonewall’s reality as not a protest, but a violent riot that was widely supported by people in the local community.

“Bottles, rocks, and other heavy objects were soon being hurled at the police, who began grabbing people in the crowd and beating them in retaliation. Weekend partiers and residents in the heavily gay neighborhood quickly swelled the ranks of the crowd to more than two thousand people, and the outnumbered police barricaded themselves inside the Stonewall Inn and called for reinforcements,” Stryker wrote. “Outside, rioters used an uprooted parking meter as a battering ram to try to break down the bar’s door, while other members of the crowd attempted to throw a Molotov cocktail inside to drive the police back into the streets.”

“Minor skirmishes and protest rallies continued throughout the next few days before finally dying down. By that time, however, untold thousands of people had been galvanized into political action.”

Violent resistance to oppression still exists today, including among trans activists internationally. In early 2025, the Mexican sex workers’ activist group Alianza Mexicana de Trabajadoras Sexuales protested two judicial buildings in Mexico City after the man who tried to murder transfeminine activist Natalia Lane was set to be released.

A screenshot from a video of the protest, depicting a protester smashing a window with a hammer. The video is posted on Instagram by user maximmagnus.

Lane, who was stabbed in mid 2022 by a man named Alejandro “N,” openly revealed that this assault was motivated by pure transmisogyny. A local magistrate allowed Alejandro to remain under house arrest amid the case, threatening Lane’s life and safety.

Demonstrators clashed with police and counterprotesters outside the buildings, throwing water, paint, and various objects. Demonstrators supporting Lane stormed the complex. Windows were broken, walls were spraypainted and solidarity was built. Consuelo, the mother of a trans woman murdered in 2024, spoke on how that murderer was let go and her family left without justice.

“My daughter has been dead for one year. No one knows the mental and moral damage done to us. My daughters, my grandchildren, are all left suffering. The case is incomplete,” she said to La Prensa.

In an update on TikTok in late July, Lane reported that the case is still ongoing, with Alejandro’s legal team postponing trials through continuous bureaucratic reshuffling, a process which she describes as “immensely painful, re-victimizing, and characterized by a great deal of institutional violence.”

But the action also worked. Alejandro was not released. In the weeks after the protest, the Mexico City prosecutor’s office declared that they’re still pursuing a case against Lane’s attacker.

“We reiterate our solidarity that our institution has shown since the beginning of this case. This is the first case of its type, where it has been brought before a judicial authority and recognized as attempted femicide,” the prosecutors declared in a statement issued to the independent media org Animal Politico. They added that the attacker will not go unpunished, and that they’ll continue providing support for Lane and other victims.

In response to criticisms of the militant demonstrations she’s organized Lane said, while smiling, "Look my dear, I don't debate with stupid people... I don't waste my energy on stupid people."

None of this is said to suggest that violence is the sole driver behind historical change. Indeed, many experienced in a multitude of struggles against oppression consider the way the question is often framed to miss the point: every movement has to deal with force, and none succeed by that alone.

Rather, it is to acknowledge the historical truth that just as long as there has been social unrest, so too have people brought about immense change through violence and the use of force. They may be scolded, condemned and erased by those on the sidelines, but that does not change the truth of what happened. So long as the oppressed will push against the oppressors, there will be people claiming that the real solution is for everyone to be nice, hold hands, and not step out of line.

Which is where the moderate argument against liberation stood for ages. However, over the past 15 years, think-pieces increasingly emerged online attempting to make this position seem less like ideology and more like science. Specifically, the assertion of this particular propaganda wave is that a highly-sanitized version of nonviolent protest is the only way to defeat fascism, with all major social change supposedly caused strictly by these tactics.

Interestingly, the bulk of these claims all tend to stem from a single source: Harvard political scientist Erica Chenoweth. Chenoweth, recently profiled in Harvard Magazine, is famous for running a quantitative analysis of 325 different social uprisings and coming to the conclusion that nonviolent protest works better than violent revolt at achieving change. This work, published in the 2011 book Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict alongside their colleague Maria Stephan, has evolved into a part of the modern liberal canon, justifying the status quo not as mere gentry distaste for riot and militant confrontation, but as supposed cold empirical fact.

Most notable in recent months have been a surge in articles proselytizing about the so-called “3.5% rule,” an initially offhand statistic in the book that has become a favorite of pundits everywhere. This rule, later expanded on by Chenoweth, after a reanalysis of the dataset, in a 2013 TedX Talk, alleges that it only takes approximately 3.5% of a population to make sweeping societal change. An additional corollary that Chenoweth has been sure to push is that these protesters must be nonviolent.

This piece will not focus too heavily on the population number, as it is beyond dispute that it does not always take a majority to cause immense social upheaval. Though it's worth noting that even Chenoweth hedges on this point, admitting the statistic is “descriptive… not necessarily prescriptive,” as there have been movements with more participation that failed and movements with less that have succeeded. Rather, this piece focuses on the dataset and analysis that Chenoweth deploys to create this statistic and advocate for their sanitized version of nonviolent change.

Put simply: Chenoweth’s work doesn’t hold up to the slightest bit of scrutiny.

The flaws in their analysis are numerous. They include undisclosed biases, major conflicts of interest, empirical issues, selectively leaving out key data, utilizing measures that a wide array of history and research into nonviolent struggle rejects and dismissing years of historical work into complicated civil revolts.

Given how canonized this supposed proof of liberal “nonviolence” has become, it’s worth dismantling in detail.

The undisclosed U.S. government and Wall Street backing

Note that this essay will often name this book and its arguments by referring to the first author, Erica Chenoweth. Chenoweth by no means has the monopoly on these perspectives, and Maria Stephan undeniably also has significant influence. This focus on Chenoweth is due to their careerism, based on the publication of the book, and their role as the face of liberal nonviolence research.

Most notable and egregious, the book is funded by the International Center for

Nonviolent Conflict (ICNC). Initially seeming innocuous, this itself is a major conflict of interest that is only mentioned briefly in an acknowledgements section. Chenoweth themself is a member to this day, and lists both ICNC connections and their experience as a motivation for writing this book to begin with.

The ICNC, contrary to how it presents itself, has an ideological bias intrinsic in its founders. Peter Ackerman, its founder and still president as of the book’s release, was an investment banker that built a fortune off the now-defunct Wall Street firm Drexel Burnham Lambert. In it, he worked as a senior executive in their international capital markets division. While not discussed often today, he notably invested over twice his salary into the company in its heyday – during a period where it was notoriously involved with illegal insider trading to build its capital, although the extent of Ackerman’s activities during this time is unclear. There is currently no proof that he was personally involved in insider trading, but he clearly played an integral role in this company’s fiscal development.

An image of Ackerman at a 2008 conference in Budapest. From Wikicommons.

Outside of private enterprise Ackerman had a direct interest in American foreign policy. He was co-chair of the United States Institute for Peace’s advisory board. The council is a government-backed nonprofit that requires Presidential and Congressional approval of its board, which includes the Secretary of State and Secretary of Defense. He held this position from at least 2006 up until his death in 2022, a period in which former USIP member Heather Ashby describes the organization as addressing “the nation building aspects of the U.S. military operations in Afghanistan and Iraq,” while having “nothing to do with resolving the wars through nonviolent options.”

“USIP actively supported the U.S. government in Iraq and Afghanistan after the invasions providing training to Iraqi government officials in truth and reconciliation, human rights, and dialogue,” Ashby wrote in a 2024 article for the blog Responsible Statecraft. “But USIP’s work did not move the needle nor did the increase in funding for USAID’s development work… USIP’s activities reflected the U.S. foreign policy emphasis on the war on terror and addressing the security and societal challenges in Afghanistan and Iraq.”

Ackerman himself wrote in April 2002, for the National Catholic Reporter, about his views of how to best approach then-President George W. Bush’s ‘War on Terror.’

“As President Bush moves to widen the war against terrorism, he has warned the governments of Iraq, Iran and North Korea not to make weapons of mass destruction available to terrorists -- or else, he implies, American military action against them is likely,” Ackerman wrote. “It is true that countries ruled by dictators have incubated or aided terrorists. But it is not true that the only way to ‘take out’ such regimes is through U.S. military action.”

This article, which draws from prior civilian nonviolent resistance movements in Serbia, describes how the Bush administration could stage a dictatorial coup by the “strategic use” of such movements.

He continued these thoughts in a June 2004 speech at the State Department’s ‘Secretary Open Forum,” one entitled “Between Hard and Soft Power: The Rise of Civilian-Based Struggle and Democratic Change.” In this speech, he described how the United States government could fund nonviolent resistance movements in countries whose governments they dislike.

“While external forces cannot bring civilian-based movements into existence, there is a great deal that the international community can do to nurture and sustain them,” Ackerman told his audience of politicians and warmongers. “This can be done either with sanctions targeted against elites and by continuous advocacy by human rights organizations against such abuses… What [civilians in opposing regimes] want is the tools to multiply their power, and the international community should be ready to help.”

He additionally detailed how this version of nonviolent resistance does not come from strict pacifism as a goal, but pragmatism — he simply believes this to be the most effective way for the United States to advance its interests.

“Nonviolent tactics are used for strategic purposes, whereas nonviolence described as an ethic is usually associated with pacifism. Successful, nonviolent resistance movements therefore don't depend on converting the oppressor. Instead they require a significant level of coercion, as authoritarians rarely give up power voluntarily,” Ackerman wrote without a hint of irony. “Virtually all leaders of nonviolent resistance movements would have considered a military option if it was viable… They demand nonviolent discipline so their provocations create dissension among groups their adversaries depend on. A movement can't co-opt the loyalties of people they threaten to kill or maim.”

He goes further in describing the applicability this could have to specific regimes. On North Korea, he refused to condemn violent intervention before describing how the U.S. could theoretically intervene. His ramble, ultimately, contributes to the modern fear of North Korea that plagues American political discourse.

“Nonviolent resistance is not a panacea. It's a set of tools, a set of weapons, that are used in conflict… With respect to North Korea, I would say two things. Number one, it's probably the toughest nut to crack for sure; but, at the same time, I don't think we fully understand the extent and potential for dissidence that might exist there,” he recounts, again without any irony. “I think we shouldn't assume that people rest easy with their lack of freedom, and if given alternatives and if exposed to possibilities, virtually anything is possible. You also have to work with the fact that a totalitarian regime that's been successful for long periods of time expects total cooperation, and when it doesn't receive it there's a great sense of disorientation that's exploitable.”

But according to Business Insider, Ackerman himself helped fund trainings in Egypt to stage not a nonviolent movement, but a military coup. His ideological views are also very clear: in 1995 he was appointed as a board member of the conservative Cato Institute, shaping its advocacy for years to come. This think tank is notorious for taking stances opposed to climate change and queer rights, among other far-right positions.

Particularly relevant to Chenoweth’s work, USIP described how Ackerman “built” much of the evidence for “nonviolent action, often from scratch.”

“Perhaps the most impactful among the many research projects Peter supported was Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan’s Why Civil Resistance Works,” wrote USIP member Jonathan Pinckney. “This book, the first of its kind, showed through a global statistical study what Peter had long been claiming: that nonviolent action was not just admirable but effective, not just sympathetic but strategic.”

In the book itself Chenoweth notably endorses these very sentiments from Ackerman, credits his influence and widely cites him throughout the work.

“This study strongly supports the view that sanctions and state support for nonviolent campaigns work best when they are coordinated with the support of local opposition groups; but they are never substitutes,” Chenoweth claimed. “The existence of organized solidarity groups…’ is sometimes necessary for opposition groups to enhance their leverage over the target. Lending diplomatic support to human rights activists, independent civil society groups, and democratic opposition leaders while penalizing regimes (or threatening penalties) that target unarmed activists with violent repression may be another way that governments can improve the probability of nonviolent campaign success.”

These biases, treated with the veneer of objectivity, run much deeper than one may initially suspect. This is primarily seen in how Chenoweth defines — or rather fails to define — nonviolence and violence as categories of revolt.

Chenoweth’s definitions make no sense

Erica Chenoweth delivering their 2013 TedX speech touting their whitewashed view of nonviolent action.

In Chapter 1 of their book, Chenoweth admits that most revolts use a mixture of violent and nonviolent tactics, and that rarely can one be seen fully without the other. They admit that “characterizing a campaign as violent or nonviolent simplifies a complex constellation of resistance methods.”

The work proceeds to completely ignore this, focusing on nonviolence as a “principled” set of actions including “boycotts (social, economic, and political), strikes, protests, sit-ins, stay-aways, and other acts of civil disobedience and noncooperation,” with no definition given for how each action is defined and considered.

Likewise, violence is defined as movements that aim for “revolutions, plots (or coups d’état), and insurgencies.” These movements, which Chenoweth clarifies are non-military ones in this project (wouldn’t want to upset that beacon of peace, the U.S. military) use tactics such as “bombings, shootings, kidnappings, physical sabotage such as the destruction of infrastructure, and other types of physical harm of people and property.”

Further, success is defined as achieving the movements’ stated goals within a year of its “peak” activities without any explicit external influence. Partial success is when they achieved their goals, but only with the “substantial aid” of external forces. No objective criteria is given.

While cited as an established fact by liberal pundits and activists, among a broad range of social scientists and historians who study these issues Chenoweth’s work has, to put it mildly, been ripped to shreds.

In his 2020 article, Debunking the Myths Behind Nonviolent Resistance, Alexei Anisin reveal a substantial problem with Chenoweth’s data set. Specifically, that many of what Chenoweth tagged as so-called “nonviolent” movements actually use what he characterizes as “unarmed violence,” consisting of violent acts that don’t use firearms but nevertheless can hardly be considered strictly pacifist.

For instance, the 1986 Philippine revolution against Ferdinand Marcos’ regime is commonly characterized in the book as nonviolent, with Chenoweth going as far as starting off the work with using it as a case study of a successful example. Anisin points out, however, that “there were incidents in which protesters threw stones, wooden staves, and homemade grenades as well as Molotov cocktails at authorities,” citing several historians who have dedicated their careers to studying Filipino history.

Other examples of this, he notes, include the 2000 Serbian revolution and the 2003 Georgian revolution, which too are used by Chenoweth as examples of “nonviolent” revolutions but have extensive amounts of “unarmed violence.”

In the online Appendix, Chenoweth outlines the sole objective criteria for what is considered a violent campaign. Relying predominantly on Kristian Gleditsch’s 2004 Correlates of War dataset, Chenoweth claims that if a conflict had over 1,000 deaths in battle, then it is considered violent. This means that a campaign with 999 deaths and one with 1,001 deaths will be classified entirely differently.

This criteria is, of course, entirely arbitrary, and given that each movement uses nonviolence in different ways and in different contexts alongside violence, it can hardly be said that there is a meaningful distinction between dubbed “violent” and “non-violent” revolutions in either the quantitative or qualitative sense. Additionally, this ignores the sheer variation in scale depending on the context this occurs in – 900 deaths in the Burmese military would be felt much more severely than 900 in the United States military.

Chenoweth, of course, dismisses these complaints by appealing to their own research, simply saying that they consulted other “nonviolent scholars.” These scholars are not explicitly named, but can be presumed to be their ICNC colleagues, given those outlined in the acknowledgements section. In essence, their defense boils down to “just trust me.”

A slew of cherry picking

The authors’ reliance on bizarre, subjective definitions is far from the only problem with their work. Why Civil Resistance aims to disregard the role that authoritarian regimes and structural factors play in determining the outcome of revolts, and instead expressly aims to center “nonviolence” versus “violence” as the dominant factor.

Political scientist Fabrice Lehoucq in his paper Does Nonviolence Work? provided an eloquent and careful deconstruction of how Chenoweth and Stephan disregard much of the scholarship in the field, and instead settle for a low quality quantitative analysis that relies heavily on cherry-picked examples.

“They rarely analyze the structure or nature of governments to understand whether certain types of regimes are more likely to change. They say little about distinctions among autocracies. Political systems in Why Civil Resistance Works are either democratic or autocratic,” Lehoucq writes. “Chenoweth and Stephan categorize opposition responses to dictatorship as violent or nonviolent, which is very much like characterizing relations between nation-states as diplomatic or warlike. Whether opponents began with one approach and gravitated to another or whether different groups use one or the other (or both) is a topic absent from their book. Whether movements are diffuse or centralized, whether there are moderates or hardliners, are also topics that Chenoweth and Stephan do not address.”

Lehoucq agrees with their claim that nonviolent revolt often produces liberal democracies. He disagrees, however, in the realm of dictatorships — his paper argues that, when dealing with authoritarianism (as many movements, including in modern America, do), incorporating strategic violence is often much more successful than a blanket advocacy for nonviolence.

Lehoucq points out how in attempts to defend their claims of a vague, dichotomous variable being the key determinant in the outcome of social movements, Chenoweth also heavily relies on incredibly vague criteria. This variable, constructed just for their study, aims to do what Lehoucq calls an “impossible” task of summarizing all political and socioeconomic determinants in a single scale, constructing a strawman for denouncing critics.

This variable has not been validated by others in the field, and has not been used in research broadly – but rather was created just for their book.

In stark contrast, Lehoucq cites several works from experts across historical disciplines, such as Guillermo Trejo’s Popular Movements in Autocracies, which focuses heavily on indigenous revolt in Mexico throughout the 20th century.

“Unlike Chenoweth and Stephan, however, Trejo takes regime dynamics seriously… He argues that the choices dictators make shape whether the opposition chooses peaceful protest or armed struggle. Opposition movements, in other words, become violent if incumbents become brutal,” Lehoucq wrote. “A far-reaching conclusion of Trejo’s book disputes the claim that the opposition autonomously chooses whether a conflict becomes violent. Unlike Chenoweth and Stephan’s book, Popular Movements in Autocracies contends that the opposition organizes an insurgency in response to the government’s choice to repress its opponents.”

Most notably, Lehoucq further argues that not only was violence a key part of Mexican revolts, but that it was crucial to their success and ensuing liberation of Indigenous peoples in the region. He uses this as a basis to level a major critique of the dataset underlying Chenoweth and Stephan’s work: it’s missing countless historically significant revolts from across Latin America.

In some analyses, Lehoucq writes that their dataset is forcibly halved owing to a mixture of missing information and a lack of adequate data on things like election quality and income. They are inevitably going to miss key information on street marches and occupations, which details a fundamental flaw with this style of analysis.

He goes further, however, in noting the sheer amount of campaigns that Chenoweth’s dataset lacks.

“The first conclusion to draw is that the database fails to include thirteen of the twenty-six campaigns on the isthmus, eleven of which were nonviolent. None of these campaigns, I should add, requires reading obscure Spanish-language sources,” Lehoucq detailed. “Several books exist on the 1948 civil war in Costa Rica. At least two books exist on nonviolent campaigns in El Salvador. And, while information on Guatemala is scarcer, a comprehensive dissertation and a handful of books exist on protest, violence, coups, and politics between 1920 and the mid-1980s.”

This mirrors the findings of Anisin, who argues that not only are numerous other 20th century revolts left out of Chenoweth’s dataset beyond the borders of Latin America, but that there is no empirical reason to exclude resistance efforts in the 19th century, the vast majority of which involved considerable violence.

This demonstrates the biased approach of the study, with Chenoweth and Stephan trying to find evidence for their pre-existing beliefs by constructing the data to reflect what they believe ought to be true. Anisin argues that the updated dataset paints a different empirical picture from what is outlined, something also supported by Lehoucq.

“The Central American data, if generalizable, modify Chenoweth and Stephan’s

claim about the effectiveness of nonviolent campaigns. Eight of the thirteen cases

they overlook are failures, and seven of these eight are nonviolent. When we include

these omitted cases, the success rate of nonviolence falls to 42 percent, well below the 60 percent claimed by Chenoweth and Stephan from their sample of cases,” he concludes in his paper. “The success rate for nonviolent action is not much higher than for violent campaigns. Two of the nine of my sample are successful campaigns; when we combine successful and partially successful campaigns, the rate is 41 percent, which is statistically no different from the success rate of nonviolent campaigns.”

Lehoucq goes further — he points out that they erroneously classify some violent campaigns as unsuccessful, such as the Nicaraguan resistance against the Somoza government, one widely regarded by scholars as successful. He identifies that it is impossible to separate structural factors from the success and failure of movements to resist dictatorships, and cites other scholars who demonstrate the importance of this internationally.

Lehoucq in a 2021 academic conference about violence in Mexico. Screenshot from the University of Pittsburgh’s Center for Latin American Studies’ recording.

Other academics make similar suggestions. Researchers Mohammad Ali Kadivar and Neil Ketchley argue in their 2018 paper Sticks, Stones, and Molotov Cocktails: Unarmed Collective Violence and Democratization that the focus of nonviolence versus violence is a red herring, with the majority of often-cited nonviolent movements containing some ignored instances of unarmed violence, similar to Anisin’s conclusions.

By arguing that a ”strict adherence to nonviolence may be significantly less consequential to the outcome of a democratization campaign than whether participants take up arms,” Kadivar and Ketchley reveal that many oft-cited “nonviolent” campaigns often relied heavily on unarmed violence. Their overview of the data provides a very different angle in the violence versus nonviolence debate by focusing on unarmed violence.

Among their examples are the 2011 Egyptian protests, the Chilean resistance against Augusto Pinochet, the Madagascar protests against President Didier Ratsiraka, the South African anti-apartheid movement, the 1980s Polish Solidarity movement, and the 2000 Serbian resistance against Slobodan Milosevic.

Kadivar and Ketchley draw from each of these resistance efforts to formulate the category of unarmed violence, something that includes instances of rock-throwing, molotov cocktails, fighting police officers, burning police stations, riots, sabotage and hand-to-hand combat. Notably, this concept specifically excludes firearms and open armed warfare.

Chenoweth and Stephan don’t discuss any of these. To their credit, they do have four chapters discussing specific case studies of revolutions in Iran in 1979, Palestine in 1992, the Philippines in 1986, and Burma (now Myanmar) in 1990. As the specific peculiarities of these revolutions are beyond the scope of this article to discuss, they won’t be explored in detail. However, as has been and will continue to be illuminated, Chenoweth and Stephan aren’t particularly credible historians, and so interested readers are advised to read histories written by, or that give strong credit to, people from these regions, as these provide much more detailed recounts for a broader audience.

Nonsensical definitions of ‘successful’ resistance

One of the clearest problems with Why Civil Resistance Works is its definition of “success.” The book uses two binary variables for defining success: one of total success, and one of partial success.

“Whether the campaign achieved 100% of its stated goals within a year of the peak of activities. In most cases, the outcome was achieved within a year of the campaign’s peak. Some campaigns’ goals were achieved years after the ‘peak’ of the struggle in terms of membership, but the success was a direct result of campaign activities. When such a direct link can be demonstrated, these campaigns are coded as successful,” Chenoweth and Stephan claim. “Whether the campaign achieved some of its stated goals within a year of the peak of activities. When a regime makes concessions to the campaign or reforms short of complete campaign success, such reforms are counted as limited success.”

Such a definition makes numerous dubious assumptions, most notably that there is a single unified agreement on what constitutes success within an allotted timeframe — something highly dubious since there are often multiple distinct yet interconnected movements pushing for a similar goal over time, each making gains or building for further efforts. Chenoweth’s definition of success appears to draw more from the timeline of non-profit complex grant cycles than any actual history of social struggle.

The American civil rights movement, for example, did not occur within one year. Instead it took decades of continuous resistance across the country, each group and action hammering away at segregationist regimes and pervasive racism.

Or even take one of the examples favored by Chenoweth and Stephan: the Iranian anti-Shah revolution of 1979. This movement consisted of numerous distinct groups, including Marxist-Leninist groups, religious fundamentalists, milquetoast liberals, and even a few disparate anarchist formations. While there was a common goal to overthrow the monarchy, it was hardly a unified movement. The leftists were later purged en masse after the revolt.

There are other problems with this definition as well. Many campaigns do not have a single, unified goal. While members of the Bolsheviks in pre-Soviet Russia may have in brief periods temporarily worked with anarchists of the time to overturn the Czarist regime, they hardly can be said to have a true, cohesive goal beyond that overthrow (and, later, that of the provisional government that briefly succeeded it).

To label their actions as having one goal is naive. This, too, can be seen in regions such as Palestine, which feature multiple distinct groups vying to achieve different angles of liberation — some pushing for anarchy, some pushing for a single Marxist state, some pushing for a neoliberal two-state solution, others pushing for a more religious state, or centrist nationalism, mirroring some of Palestine’s neighbors.

The only way one can create a monolithic definition of “success” here is by crowning a single part of the movement the effective “leaders” of it, something intensely disconnected from the on-the-ground reality.

Further, this definition presumes the continued existence of what the authors consider a liberal democratic state, or at least the push for one. This is seen in how the push for nonviolence in many cases is represented as a success through getting the existing state to meet the demands of the given revolt.

This represents more of their unspoken ideological biases, with the influence of America and Western nations seen as the default, their governmental structure ideal, a final stopping point in societal growth rather than being one more way hierarchy and authority manifests across history. This is an important distinction: were Chenoweth in the 1600s, perhaps they would consider revolts to establish a new kind of monarchy as something to strive for.

Notably, this definition also results in a form of victim blaming, with the loss of civil rights or liberation in many cases being attributed to the oppressed not doing the right thing. This is riddled throughout the book book in a quite explicit way. In Chapter 1, they state with grave, offensive inaccuracy that a failure of the oppressed to consider nonviolent resistance failed to stop the Holocaust.

“The claim that nonviolent resistance could never work against genocidal foes like Adolph Hitler and Joseph Stalin is the classic straw man put forward to demonstrate the inherent limitations of this form of struggle,” Chenoweth and Stephan scold. “Collective nonviolent struggle was not used with any strategic forethought during World War II, nor was it ever contemplated as an overall strategy for resisting the Nazis. Violent resistance, which some groups attempted for ending Nazi occupation, was also an abject failure.”

Chenoweth, of course, fails to consider the numerous examples of successful violent resistance that led to detainees escaping from concentration camps and sabotaging the Nazis from inside. Or the ultimate defeat of the Nazis came from a literal massive war; only a single sentence mentions World War Two as context. No serious historian of that war considers the many, many armed anti-Nazi resistance movements to have played no role in their defeat.

For a tangible example, one only needs to look at the Bielski Partisans, a group of several hundred Jewish radicals known for their violent revolt against the Nazis. According to the U.S. Holocaust Museum they saved over 1,200 people. This is through a variety of different tactics, including covert missions to liberate people from ghettos, creating permanent base camps deep in the swampy regions of Naliboki Forest, and relying on armed guards to protect the more vulnerable members of their survivor group.

The Bielski Partisans in 1944 while in the Naliboki Forest. Photo from the Holocaust Encyclopedia.

The Partisans also demonstrated a core understanding of the need for mutual aid and a wider ecosystem of survival and resistance. Just as they had armed guards prepared to fight Nazis, so too did they include people who never raised a single weapon, instead working in bakeries, synagogues, tailors, carpenters, schools and medical clinics. They even had their own courts. They survived through hazardous weather, raids on Nazi-occupied cities, and even a typhoid epidemic, which due to this ecosystem of survival had only one casualty.

Readers interested in learning more about Holocaust resistance groups are advised to read works such as Serafinski’s Blessed is the Flame, a historical work examining how these means of resistance are effective even in concentration camps. Many prisoners were not only able to fight back against guards with mass resistance, but they were also able to escape death and live full lives. Of course, many others failed, but to blame this on the usage of violence when their lives were threatened by overwhelming odds is nothing short of grotesque.

Chapter 3 sees more of this. In it, Chenoweth and Stephan discuss the problem of endogeneity, or the idea that violent campaigns only emerge after nonviolent ones fail. To rebut this idea, they first begin by suggesting that no one should ever go violent, and that if they failed in nonviolence, people failed to “maintain their commitments,” and that this is why they did not succeed.

They do not outline where the cutoff is for having “tried everything,” because the argument here is that one can never stop trying the same tactics over and over, so therefore they need to keep being “nonviolent” if they want to be successful. Any deviation from this, they suggest, is a failure of the oppressed. This is an argument clearly formed while sitting in academic offices, far removed from the blood and grief of actual struggle.

The victim blaming here is self-evident, as when Chenoweth writes about Palestinian liberation they suggest that when nonviolent campaigns failed, violent ones came in and made things worse entirely because of internal turmoil. Nevermind, of course, that this division is patently false. The nonviolent 2018 Great March of Return, for example, drew broad support, including from groups that had previously mostly focused on violent tactics. It was brutally crushed by the Israeli regime. There are simultaneously multiple distinct Palestinian resistance groups at any given time, using a wide range of tactics, with some actors even funded or influenced by Israel’s interests.

The open biases in these sections increase drastically, practically to the point of anti-Arab racism. Chenoweth argues that Palestinians failed to take deals for independence previously, that they just rebelled out of “futility.”

“For example, although many Palestinians question the ingenuity of the offer, several Palestinian groups responded to Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak’s offer of independence for the Gaza Strip and most of the West Bank, which was accompanied by settlement expansion and other provocative Israeli actions, with an unprecedented wave of violence,” Chenoweth and Stephan write. “Thus, violence is not always a last resort, nor do insurgents readily discard it when it has proved fruitless.”

As Israeli journalist Gideon Levy describes in his 2024 book The Killing of Gaza, Barak — and other Israeli politicians who claimed to offer Palestinians peace — was doing this amid relentless bombings and murders of civilians. He himself directly sabotaged that effort through continued violence and subjugation. Indeed, as corroborated in 972 Magazine, Barak was disingenuous in any claims for peace with Palestine.

“All the premiers sided with continuing the occupation and the siege on Gaza,” Levy reports. “None of them thought for a moment to allow a real Palestinian state, with full powers, a state like any other. It didn’t occur to them to liberate the Gaza Strip from the strangling siege. Had it not been for all those, perhaps there would not be a Hamas.”

American sociologist Jeremy Pressman provided a detailed analysis of the problems with how scholars of nonviolence, and Chenoweth in particular, characterize Palestinian resistance to Israeli occupation in his 2017 paper, Throwing stones in social science: Non-violence, unarmed violence, and the first intifada. Analyzing all the evidence available at the time, he concluded that much of the literature and discussion on this topic is obfuscated by a need to reduce a common resistance tactic of stone throwing into either a strictly violent or non-violent category.

While his conclusions on Palestinian liberation lean towards the prescriptive in saying what they ought to do to be seen as “legitimate,” he nevertheless makes a compelling point on how these nonviolence researchers offer a reductive perspective on Palestinian history.

“In Chenoweth and Stephan (2011), the first intifada is one of hundreds of cases. Coding this one case does not change their overall conclusion about the greater efficacy of non-violent protest,” Pressman wrote. “This also suggests to me a related question about work on non-violence: What do readers have in mind when scholars tell them about non-violent events or campaigns? I doubt that they assume such interactions involve unarmed violence, an analytically distinct category from non-violence.”

Indeed, this need to characterize the complexities of distinct, disparate international movements of revolt across a period of decades shows a naive approach to the research that neglects the intricate and meticulous approach needed to sufficiently analyze causation in each of these movements.

We can bear witness to real, tangible consequences of this push for a docile, sanitized nonviolence, both within the trans rights movement and beyond. Earlier this year, amid an increase in trans people buying guns and teaching each other self defense as attacks on us get worse, trans news outlet Assigned Media published an article that advocated against gun ownership, citing Chenoweth as justification for the “right” way to protest.

Using Chenoweth’s work to lecture activists against pursuing meaningful revolt has also been deployed by the New York Times opinion section and an a LGBTQ Nation article (which also misgenders them) published earlier this year. This approach is also favored by national nonprofits like the Center for American Progress, who cite the 3.5% rule as gospel, and is even pushed by Pod Save America, one of the biggest political podcasts in the country.

We’re already seeing this play out in tangible, damaging ways in protests against the Trump regime. This year saw the 50501 group gain national headlines and the support of numerous nonprofits and more centrist activists, including queer ones. In justification of their methods, they cite Chenoweth on multiple occasions, curiously without making any statements on revelations that organizers proudly work with cops and have even called the police on a Black activist in Los Angeles.

Similarly, some organizers of the No Kings protests — partnered with 50501, the ACLU, the Human Rights Campaign, Greenpeace, Indivisible, and ‘democrats.com’ — have repeatedly cited Chenoweth’s 3.5% rule as an inspiration.

Similarly not mentioned in most news coverage is how some No Kings organizers have repeatedly and proudly worked with cops, in spite of the fact that numerous protesters have been arrested, with protesters in LA shot at by police. One man was even killed, though it’s unknown by who.

To be clear, plenty who showed up to these protests did so in good faith, wanting to show their resistance to a fascist regime. The connections plenty of on-the-ground folks made during them are inarguably beneficial. But those leading the protests — and often seeking to co-opt them — do so from a set of false assumptions that will endanger and weaken the very resistance they claim to value.

Tellingly, a recent Electronic Frontier Foundation report revealed that nearly two dozen agencies mass surveilling the public during the 50501 and No Kings protests. Through these searches of public and private information they collected an incredible amount of information on protesters across the country, who often were not properly taught operational security, marching without masks and with tattoos visible.

Some No Kings marches even encouraged people to “RSVP.”

An image of a protest flyer of ‘the solidarity wave’ that circulated widely on social media made in direct response to a popular ‘sit-down wave’ that promoted a sanitized version of ‘nonviolence’ that included literally turning people over to the police..

Why Civil Resistance Works is simply a piece of propaganda masquerading as though it’s a legitimate scientific work. Its place in the canon of today’s liberals does little more than excuse hierarchical, capitalistic power structure as something innate to human existence, portraying any militant resistance as automatically hopeless.

Authoritarianism and capitalism are not the default status for humanity, and in fact haven’t even existed for much of our existence on this planet. We are a social species, and our default state is to care for one another. This caring impulse is the exact thing that literature deifying a passive nonviolence seeks to seize upon, hijacking our empathy for each other as a way to sabotage revolt.

None of this means that we need to pick up arms and start randomly looking for a fight either. Once again, those experienced in these struggles regard a simplistic binary between “violent” and “nonviolent” resistance as a false one.

There are solutions to oppression that are grounded in history, ones that have worked across time and space. In this article’s second part, we will grapple with some real world examples of revolt against oppression, and show just how much we have to learn from our siblings in solidarity.

-Edited, and contributed to, by David Forbes

Important message from TNN

Trans News Network operates on a shoestring budget without any ads or paywalls, leaving us with a small fraction of the resources of mainstream newsrooms. We rely on your continued support to publish articles like these in the face of escalating government censorship of the press.

If this article benefited you or someone you care about, please consider chipping in with a paid subscription, contributing a tax-deductible donation of $28 to our fundraiser, or referring a friend to TNN by sending them this link if you can’t afford to donate. We appreciate you all so much–your support really keeps us going.